It’s become something of an accepted truth. We need a knowledge and awareness of the global marketplace if we are to be successful in business today. Why is that? What insights will this knowledge grant us? What business skills will this awareness enhance? How will our understanding of things global contribute to our success?

Oh, and when we hear about the global marketplace and words like globalization, what, exactly, do those terms mean?

The broader term, globalization, can take on several meanings depending on the context in which it’s being used, but as far as business is concerned, globalization refers to the movement of capital, labor, goods, services, and intellectual property through trade, across international boundaries. That’s a mouthful and there are political, social, cultural, technological, and environmental aspects to globalization, but to begin, let’s stick to business.

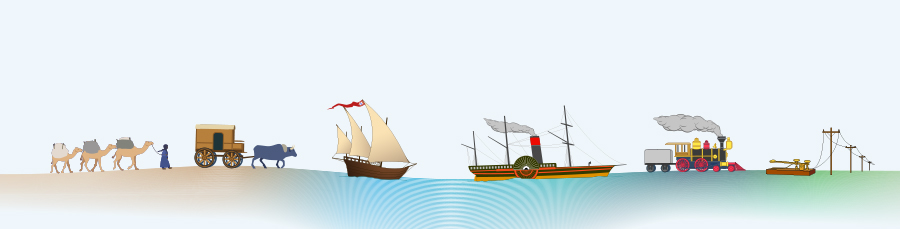

Speaking of beginning, the term globalization came into wide use in the early 1990s, but if we’re talking about international trade, some scholars argue that the first form of international trade began in the third millenium BCE between Sumer and Indus Valley civilizations—prehistoric Iraq and Afghanistan. Middle Easterners had figured out how to domesticate camels and their caravans ranged from the Mediterranean to central Asia. The Greeks, a few thousand years later, traded from India to Spain. Later, through a network of roads, written communiques, an organized postal system, and a common currency, the Roman Empire united much of the European continent and reached east as the Chinese and the Mongols reached west. Trade along the Silk Road began.

Constant wars and the money to finance them eventually weakened Rome. When the expansion of the Empire slowed, so did the influx of slave labor and war booty. When the Vandals took control of North Africa, they disrupted trade. The prosperity of the Empire was assaulted on all sides and eventually, Rome fell.

The same trade routes to the Far East that brought silks and spices may have also brought a series of plagues. Over the next few centuries, European population steadily declined. Early in the eighth century, with long-distance trade at a low ebb, European farmers had to be far more self-sufficient, and with populations lower, they had to be more labor-effective. As with every age, technology helped. Farmers learned the advantage of rotating crops. They collared horses and oxen to drag ploughs. With power from water and wind, flour was milled, lumber sawed, forges fired, and the production of goods expanded. Taken together, these advances made the manufacture of goods faster and more efficient, and with speed and efficiency comes profit. By the 1300s, the political climate had stabilized and, though punctuated by waves of plague and famine, commerce and prosperity grew.

Western Europe emerged from the Middle Ages into the Renaissance. The wealth of city states like Florence, Genoa, and Venice fueled a rebirth of mathematics, science, philosophy, literature, and, of course, the arts. The Ottoman Empire, which controlled the Middle East and most of North Africa, captured Constantinople in 1453, and shut down the Silk Road. In response, European merchants financed expeditions that pushed west and south, seeking new trade routes to Asia and the Indies.

The Portuguese modified an Arabic sailing vessel, and with that new technology, their caravels were faster and more maneuverable. With these vessels, they mapped the west coast of Africa, and circumvented the Muslim land-based trade routes across the Western Sahara Desert. Those new routes brought wealth in the form of slaves and gold to Portugal, but perhaps of greater import was the discovery of the Atlantic wind patterns. With this knowledge of the Trade Winds, Columbus set off for the East Indies. Of course, he ran into the Americas, but his voyage set off the Age of Discovery, which gave birth to a series of empires and ushered in nearly four centuries of colonization.

The race for trade and raw materials would go to those who built the strongest, fastest ships; and as ship design and shipbuilding flourished so did the maritime empires those ships supported.

The 16th and 17th centuries saw the rise of the Portuguese and Spanish and later the English, Dutch, and French trading empires. In the 17th century, trade became the province of chartered companies. The Dutch East India Company became the first multinational corporation to offer stock.

Growth in trade eventually sparked an industrial revolution that not only supercharged the global demand for goods, but also provided the technology to meet it. Locomotives sped the flow of goods across continents just as steamships did across oceans. The telegraph connected Europe and the Americas and information that once had taken weeks to relay could be transmitted in minutes. By the end of the 19th century, trade routes extended to virtually every corner of the globe.

The period between 1870 and 1914 is often called the first era of globalization. Technology made transportation and communication relatively cheap and fast. Goods no longer had to be made where they were consumed. Labor moved as well. In the mid-1800s, about 300,000 people a year emigrated from Europe. By 1901, the number reached 1 million. The passport would not come into widespread use until 1914. The British Empire, on which the sun never set, effectively became one massive free trade zone. And only in the 1990s did international capital flows, relative to the size of the world economy, equal the levels in the decade before the first World War.

That war brought a sudden and dramatic end to global trade. Viewed historically, however, this cycle of expansion and contraction is not unusual. Technology reduces costs—of communication, of transportation, of manufacturing, of distance—and periodically this trend is punctuated by periods of war, natural disaster, and protectionism.

Author Thomas Friedman talks about three stages in the development of global commerce. At first, global trade was the province of states, then the territory of multi-national companies, and now the arena of individuals. Despite the changing environment and the advances of technology, history teaches that certain commonalities hold true through time.

The first is communication

Steve Rempel, a Harbert Executive MBA and the International CIO of Walgreens Boots Alliance, talks about communication. “Fast, effective communication has always been important to global trade. Video is my new norm. I rarely make a phone call anymore,” he says. “It’s enabled a level of detailed sharing that a few years ago would have been impossible.” According to Rempel, this level of communication allows the differences between cultures to fall away. “People are careful to spend the time to make sure they hear and understand correctly. We collaborate across the world.”

That collaboration is not without its issues. Just as the sun never set on the British Empire, it doesn’t set on a multi-national corporation. Rempel again: “The technology can help us communicate, but you have to understand that it’s not like walking down the hall. 9 a.m. in London is 4 a.m. in New York. The working hours don’t line up. We spend a lot of time planning. You have to plan up front and document expectations. It’s at a much deeper level of execution. If you’re running for FedEx, you’re already behind.”

And then there’s technology

Enterprise Resource Planning is a set of management software programs that let businesses automate and streamline the so-called “back office” functions by incorporating information from the various facets of an operation into one database. This software can let the business owner—literally—do more with less. Over the years, ERP has become mobile, moved to the cloud, and connected to social media. But as artificial intelligence and machine learning come online, the software itself can learn and change to better manage business operations. Again, speed and efficiency.

Blockchain technology can maintain a permanent, tamper-proof record of transactions. Global trade goes through the hands of a number of stakeholders—exporters, importers, brokers, banks, transportation agents, distribution centers, and government agencies. The technology secures the data and the documentation necessary to an efficient, transparent supply chain. IBM and Maersk have established “a joint venture to provide more efficient and secure methods for conducting global trade

using blockchain.”

With that thought in mind, think partnerships

And think about two aspects of partnering. If you intend to enter a foreign market, especially one that is literally “foreign” to you, your efforts may be greatly enhanced by collaborating with a local company which knows that market—the consumers, the competition, the regulations, and nuances—better than you do. The same holds true for aspects of your business, or the business you intend to create. “Effective international trade has always been about partnerships. It used to be that countries made partnership through marriage,” says Steve Rempel. “Marry a prince and a princess and gain access to the seaport. We look for those partners who can do a job much better than we can. If we want to be the first pharmacy-led global health company, we’ve got to be very conscious of the differentiators and look for partners who are the best of the best.”

Today, as we look to the horizon, the World Economic Forum and the International Monetary Fund tell us that the expansion rate of global trade may slow. The recent hike in tariffs has impeded global trade, as has China’s slowing growth and the confusion over Brexit, but a longer-term trend may be the impact of automation. As manufacturing continues to be automated, the cost of labor becomes less of a factor in the cost of production. Companies, then, will gain no significant advantage by offshoring and will choose to locate close to their largest markets. Automobile manufacturing is highly automated and all of the major European and Asian car manufacturers have plants in the US.

But while the trade in goods may slow, the trade in services is booming. It took hundreds of years for global commerce to shift from agriculture to manufacturing, but the shift from manufacturing to services can be measured in decades, even years. The speed and capability of 21st century communication has made this growth possible. Research by Deloitte tells us that “the share of total output—world GDP—accounted for by services [has experienced] a sharp increase in almost all countries. Indeed, a few countries, such as India and Sri Lanka, have broken the historical convention by heading straight to services without developing a significant manufacturing sector at all.”

This growth in the services sector carries with it a lesson. Consistent with the pattern of history, new technologies open new markets and create new opportunities for trade. Today, though, the speed of change in technology speeds the change in global trade. One creates the change that drives the other. And it’s all moving faster and faster. There was one world before the internet and another world after, just as there is one world before machine learning and artificial intelligence and there will be another after. To stay abreast of change and the opportunities it presents, business men and women must keep up to date with the technologies, with the data. They must communicate clearly and rapidly across international boundaries and they must create partnerships that are agile enough to adapt to a rapidly changing environment. Just as it did centuries ago, the prize goes to the swift. Today, however, we have a whole new understanding of that word. It’s different, but the same. And a whole lot faster.