Leadership. Simple, but not easy. Clear, but often obscured by context. It requires confidence and a strong dose of humility, the steadfastness to persist and the flexibility to adapt. Confused yet?

We’ve talked about leadership for—literally—thousands of years. Early Sanskrit writings set out the various types of leaders and leadership. Socrates in the West and Lao Tzu in the East set forth the qualities of a leader, chief among them being “Know thyself.” Aristotle maintained the value of phronesis, practical wisdom—what poet Samuel Coleridge called “common sense to an uncommon degree.”

After Aristotle, Plutarch compared the lives of those he esteemed—Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar, for example—and explored the influence of character on the lives and destinies of men. He suggests that good leaders are knowledgeable, competent, fair, principled, and committed to their beliefs; that they attract followers by virtue of the elevated qualities of their character.

Leadership has always had something of a mythical quality. Think Arthur and the sword in the stone. As we move into the Middle Ages, leadership bwecomes firmly rooted in “divine right.” Leaders led, rulers ruled by the approval of heaven. Divine right hangs on for a few hundred years, but in the Renaissance, Machiavelli gets down to earth: “The first opinion which one forms of a prince, and of his understanding, is by observing the men he has around him.”

By the 1700s, as monarchies and divine right give way to democracies, historians recognize leaders as “great men” who, by virtue of their inborn qualities, assume authority and power. According to this great man theory, history itself is no more than the biographies of great men. This theory still holds sway, but with the emergence of the social sciences comes the idea that leadership is a science that can be learned and honed.

Leadership today

Today, leadership development is a $366 billion global industry. If you enter “leadership” into a search engine, you’ll get 5,420,000,000 hits. And if you search for “qualities of a leader,” you’ll find that there are fifteen qualities that make a good leader. No, eleven. Actually, there are eight essential qualities. Or is it five? But ten qualities are necessary and fourteen are fundamental.

Stepping back from the huge body of confusing, often contradictory advice and information, one might conclude that most of the leadership “experts” don’t really know how to improve leadership skills.

And research bears it out. According to a study by consulting firm McKinsey and Company, most leadership development efforts fail. In spite of the $366 billion spent worldwide, only 7 percent of CEOs believe the efforts pay off. Stanford professor Jeffery Pfeffer is direct. Leaderships training is “BS.”

The BS

No question, leadership development is fraught with problems. First, there’s the enduring notion that leaders are born, not made. As a consequence, there’s an aspect of leadership development that studies these so-called born leaders, catalogues, codifies, and distills the behaviors of these model leaders and then attempts to impart those behaviors. But sometimes great leaders exhibit many of the same traits as psychopaths. Maybe not what you want to emulate. Alexander isn’t great if he’s conquering you. Then, he’s Attila the Hun.

With “fundamental skills approach,” there’s the one-size-fits-all trap. An Army general operates in a vastly different environment than a business leader or a movie director. Both confront complex, messy situations. Both encounter risk. Both depend on teams to accomplish goals, but each has a vastly different relationship with those they lead. Context is important. One size of leadership development does not fit all.

And then there are the inherent issues with typical training methods. A motivational book and a three-day retreat may be interesting and entertaining, even inspiring, but will have little or no lasting impact. If we believe that leadership is a learned skill, then it will require practice, feedback, and coaching—and, yes, failure. You don’t learn how to ice skate by reading a book, discussing the qualities of great skaters, or even looking at the physics of skates and ice. You gotta get out on the ice and risk a fall or two.

Next are the biases, the assumptions that leadership trainees (and leadership teachers) sometimes bring to the task. Note: A job title does not make a leader. Good leadership is not automatically conferred with position and authority. Subject matter expertise does not make a leader. Particularly in today’s rapidly changing business environment, the know-how that may have prompted a promotion will quickly become obsolete. By the way, “earning” a position—by whatever means—doesn’t make a leader.

And businesses often compound the problems by failing to measure leadership. Certainly, good leadership is difficult to quantify. Attempting to put exact numbers to creativity, communication, emotional intelligence, and commitment is virtually impossible. That said, one can see the evidence of effective leadership. Is the team happy and productive? Is communication open and transparent? Do team members and employees understand the firm’s mission and goals and know they have input into how they are realized? Do team members move up in the organization? Is retention high? This evidence may open a door to measuring and managing leadership development.

Perhaps the greatest obstacle to leadership development, ironically, is a company’s leadership. “Companies and their leaders are consistently inconsistent,” says Bill Shannon, a 20-year veteran of Disney who is now Auburn’s director of HR development. “If the effort to develop leaders doesn’t work from the top down, it doesn’t work. Effective leaders model the way and align with the organization’s core beliefs and strategies . . . You can’t drive a car that’s out of alignment. It’ll run off the road.”

Obstacles aside

If you possess a commitment to work and willingness to risk failure; if you have the patience and persistence to practice; a degree of self-knowledge, if not humility; and the disposition to look unflinchingly at the results of your efforts, you may be prepared to hone the qualities and acquire the skills of effective leadership.

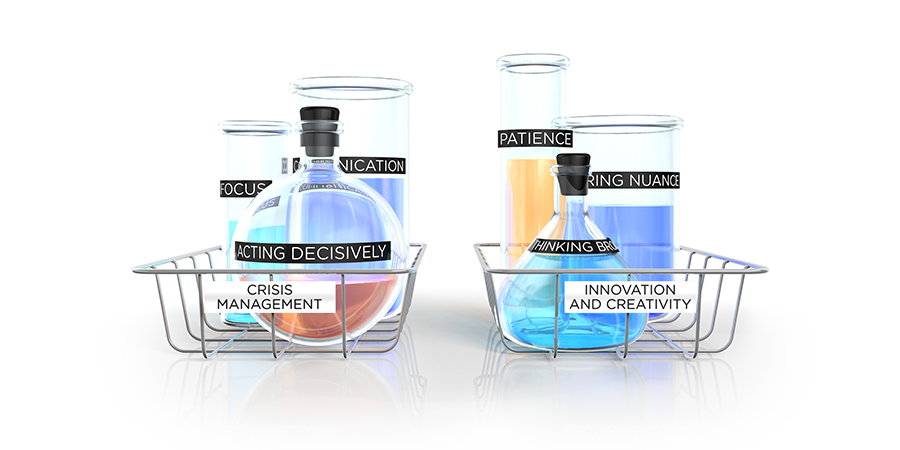

It may be a small point, but let’s distinguish qualities that good leaders possess from skills they need to do their jobs. For the sake of discussion, skills are the tangible abilities that are necessary to address the challenges specific to a particular environment. If you’re managing crisis, focusing quickly, communicating concisely, and acting decisively are vital. If you’re promoting innovation and creativity, thinking broadly, exploring nuance, and acting with patience and emotional intelligence rise to the fore. Context again. In these examples, the specific skills may differ, but the basic qualities of a good leader—the integrity to inspire trust, the flexibility to handle the unknown, the awareness to empower others, to nurture growth—are common to both leaders, to both environments.

The Army tells us that the building blocks of leadership are character, competence, and commitment, and that these qualities develop through experience. In fact, the careful, repeated practice of leadership skills, the Army maintains, leads to the development of these qualities. “People have the potential for leadership as long as they are capable of learning from their experience,” says Bernie Banks, associate dean for leadership development at Kellogg. After a 25-year career, he retired from the Army as a brigadier general. He cites an “empirical construct” developed by the Center for Creative Leadership as a model for how leaders should be trained.

“70% of . . . leader development is the challenging assignments and experiences that one has amassed. 20% is developmental relationships . . . And 10% comes from formal coursework and training.”

One piece is not more valuable than another, he maintains. Experience, mentorship training, and the study of theory create a balanced whole. “In total, these three things account for how a leader develops.”

Each of us likely possesses some of the elements of leadership and, as Banks indicates, these develop with time and experience. They first manifest themselves in the “craft” of leadership—the basic, necessary skills. They might be called technical or management skills—goal setting, directing, organizing, coordinating, etc. These skills often get a bad rap, but shouldn’t. Though leadership goes beyond these basic skills, without them the leader is “an idea person” who may be able to think “great thoughts,” but can accomplish nothing.

To these basic technical skills, the leader adds less tangible, but no less necessary, soft skills. The courage to learn and grow probably tops the list. Unfamiliar or new situations usually create apprehension, but innovation and creativity lie in the realm of the unfamiliar and the new. With experience and repetition, a leader can develop the mindset to learn the unfamiliar and embrace the new. Disruptive innovation (isn’t all innovation, by definition, disruptive?) has become the way of the world and as these disruptions redefine business models, leaders who are willing to learn, change, and grow can shape the future, not just react to it.

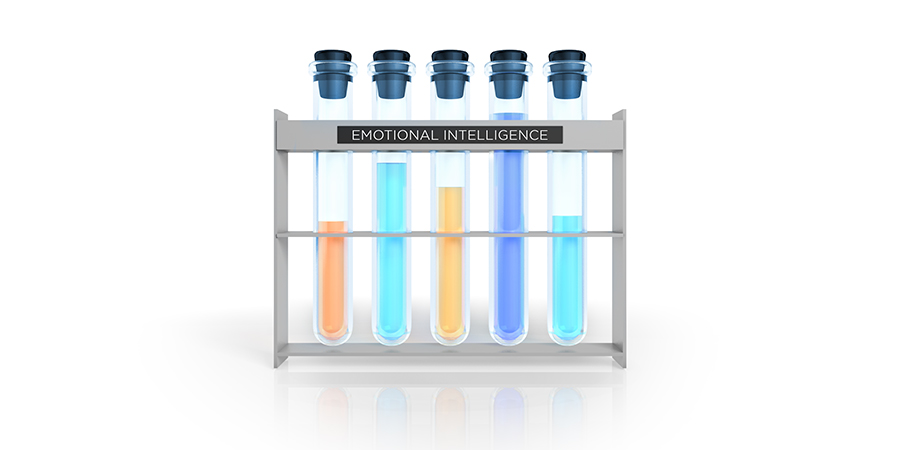

Over the last decade or so, emotional intelligence has emerged as a key leadership skill. Psychologists John D. Mayer and Peter Salovey define the term: “Emotional intelligence is the ability to accurately perceive your own and others’ emotions; to understand the signals that emotions send about relationships; and to manage your own and others’ emotions.” It has five key elements:

Self-awareness:

the ability to understand yourself and your effect on others.

Self-regulation:

the ability to moderate your reactions, to think before acting.

Motivation:

a passion for work that goes beyond money and status.

Empathy:

the ability to understand the emotions of others.

Social skills:

the ability to manage relationships and build networks.

New York Times science writer Daniel Goleman says, “It’s not that IQ and technical skills are irrelevant. They do matter, but mainly as ‘threshold capabilities’; that is, they are the entry-level requirements for executive positions. But my research, along with other recent studies, clearly shows that emotional intelligence is the sine qua non of leadership. Without it, a person can have the best training in the world, an incisive, analytical mind, and an endless supply of smart ideas, but he still won’t make a great leader.”

And, of course there’s the ability to communicate—which is more than emails and executive orders and clearly delineated expectations. To the good leader, it’s the ability to influence, to motivate. Yes, memos, directives, and presentations are important, but leaders must be good storytellers. Princeton neuroscientist Uri Hasson writes that “a story is the only way to activate parts in the brain so that a listener turns the story into their own idea and experience.” Think TED Talks. Life happens in stories. We connect to each other through story. A well-told story can inspire its audience to act because it takes them to a place that numbers and analytics cannot go—the realm of the heart.

The development of any one of these skills is a treatise unto itself, but despite the depth and complexity, each can be refined by study and practice, by work. There are no shortcuts.

Craft and art

Truly great leadership may be elusive because, at its best, leadership—like painting or music or writing—is a creative act. It moves past craft to art. Craft can be commoditized, mass-produced. And in large part, that’s the aim of most of leadership development. Find the basic elements of the thing. Standardize it and repeat it. Commoditize it.

Art resists such commoditization. You can learn the skills, and after you’ve mastered them and experienced enough, you may be ready to create, to practice the art of leadership. Artful leaders like Steve Jobs, Indra Nooyi, and Richard Branson surprise us with their magic. They pull the sword out of the stone.

Most artists will tell you that a great work of art is simple, focused. It’s about one thing. One central idea runs through it from beginning to end. It may be that those who practice the art of leadership have found that one thing. Bill Shannon will tell you that the one thing is a core belief; “Your belief drives your process and your process drives your successes.”

Simon Sinek, now a well-known leadership author, came on to the leadership scene in 2014 with a landmark TED talk. He tells us that; “Every single person, every single organization on the planet knows what they do, 100 percent. Some know how they do it . . . But very, very few people or organizations know why they do what they do. And by ‘why’ I don’t mean ‘to make a profit.’ That’s a result . . . By ‘why,’ I mean: What’s your purpose? What’s your cause? What’s your belief?”

This core belief, this essential “why,” distinguishes leaders. Sinek points to Apple, whose central idea is the relentless refinement of design. It may be a computer company that makes hardware, but we don’t buy Apple products for the specs on their gear. We buy them because we value what they believe and want to be part of it. Sinek:

“We follow those who lead, not because we have to, but because we want to. We follow those who lead, not for them, but for ourselves. And it’s those who start with ‘why’ that have the ability to inspire those around them.”

No shortcuts. To be a leader, first master the craft. To be an artful leader, find your why, your one thing. Simple. Not easy, but well worth it.