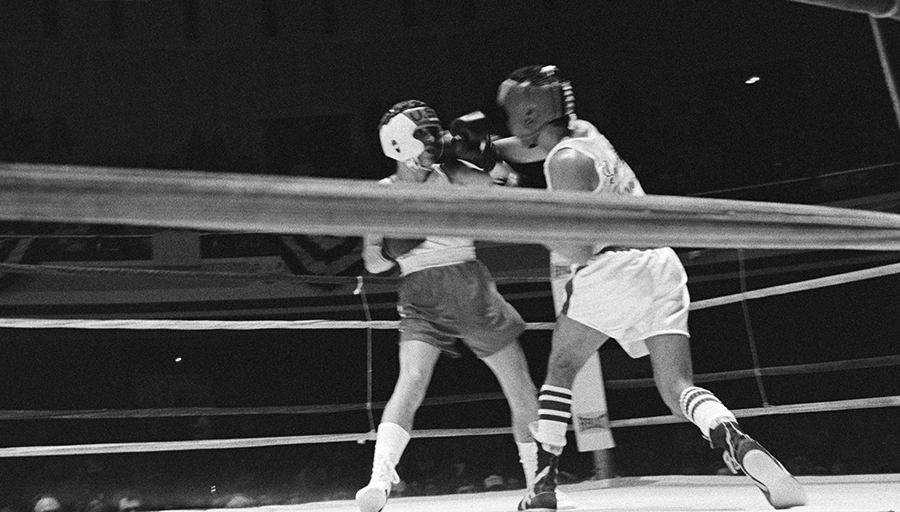

Mike Tyson: “Everybody’s got a plan until they get hit.” Well, the events of the past few months have swung at us pretty hard. Some of us got knocked flat, some are standing but reeling from the blow and some managed to slip the punch altogether and pivot out of range.

usiness thrives on stability. Plan, put a system in place, tweak the system successively, maximize efficiency, and grow methodically. It’s not unusual that businesses, when confronted with sudden uncertainty, i.e. crisis, react reflexively. They hunker down, reduce investment, cut research and development, freeze hiring. It’s a totally predictable response. Typically, humans don’t run screaming like they do in the movies, they freeze in a defensive posture.

In the immediate short run, this cover-up-and-protect posture may be necessary. But when we adopt it, we’re not reacting to the next punch, we’re reacting to the last one. No situational awareness. If you stay in one place and don’t move, you’re gonna get hit again.

The military is well aware of the axiom that no plan survives first contact with the enemy. Dwight Eisenhower remarked that “Plans are useless, but planning is indispensable.” He recognized that strategic planning must be dynamic—able to react to a fluid, changing environment—and only by planning and rehearsing many possible scenarios can the strategist take advantage of the unexpected.

While multi-team scenario planning may be beyond the financial and labor resources of smaller businesses, thinking about the future and exploring the strategies that will move the business forward is not. Plans must be redrawn as circumstances change and business planners, like their military counterparts, should manage planning at three levels: strategic, operational and tactical. No surprise here. But it is valuable to understand that a crisis environment can quickly elevate a tactical loss to a strategic issue, and leaders must constantly re-evaluate plans and actions.

Modern military practice has adopted the concept of mission command—centralized intent and decentralized execution. For business, it’s the responsibility of the C-suite to clearly and simply communicate intent and to ensure that managers and workers know how their individual areas fit into the larger system. Once set in motion, managers and workers can react to changes quickly, without waiting for specific directions from on high. This strategic concept requires clear communication, trust and a flexible hierarchy. It yields speed, adaptability and resilience, vital qualities for dealing with crisis and disruption.

Rebuild On Your Values

Key to success is the leader’s responsibility to maintain a broad situational awareness. Know what’s going on inside your business—your balance sheet, your cash flow, your employees and your physical plant—take pains to understand your environment, but above all, stay close to your essential value proposition and your customers. What do they want and need? And how, in a time of crisis, have their wants and needs changed?

Many of the changes that were seemingly wrought by the pandemic were already underway, and under the pressure of the pandemic, these changes are being realized faster. Robotics were on the horizon; now one-fifth of Amazon’s work force are robots. Retail stores have long been under threat from e-commerce. Now malls are closing and even recognized department stores like Lord and Taylor and Neiman-Marcus are circling the drain. In the age of COVID, telemedicine has leapt forward and at most schools online education, once an occasional alternative, is now a mainstay.

The pandemic has hit the food service industry particularly hard. Without customers, restaurants have closed, staff have been laid off. Some businesses are now gone forever. Some are holding on, offering takeout and delivery, but delivery services can cut deeply into takeout profit and leave the restaurant just running in place.

Chef Eric Rivera found another way. Sensitive to his customers’ needs and his own skill sets, he pivoted and diversified. He immediately shifted to pickup and delivery, but used his own staff. His menus had always been different—a range of price points and a variety that changed with the availability of different foods. This variety and variability—this diversity—stands apart from most restaurants, whose menus rarely change and whose price points are similarly fixed.

With relatively cheap comfort food at one end of his offerings and higher end dining experiences at the other, he expanded his customer base. He did the same thing with his order structure. Customers can buy a single meal, a bottle of wine or a weekly package. It’s not just soup to nuts, it’s a lot of different soups to a lot of different nuts. Rivera pivoted around his core competency and deliberately created a diversity of offerings that expanded his customer base.

Technology makes much of this variety and customization possible. Rivera publicizes his offerings and follows up with his customers through social media. He employs a payment processing system that allows diners to purchase food and drink online. Tips and delivery charges are built in. In effect, he’s “retailized” his business and discovered an unanticipated benefit. He cooks to order. No guessing how many customers may show up on a given evening, how much staff is necessary or how much food to order. In much the same way a retail operation logs a sale, tracks its inventory and plans replenishment, Rivera, given his order data, knows what he needs—food, labor, time—to serve his customers.

Pivot quickly, diversify your offerings, stay close to the customer and your own unique value proposition, take full advantage of technology. Rivera’s making more money now than before the pandemic.

Wolfgang Puck has a much bigger operation than Eric Rivera, but his experience is similar. He pivoted to takeout. At first, he focused on delivering food, but quickly found that his customers came to his restaurants as much for the dining adventure as they did for the food. “I said let’s bring them [our customers] the adventure of having a meal with us.”

He now orchestrates drinks, wine, appetizers and desserts around a central entrée. He offers wine and cocktail packages, custom-cut meats, virtual cooking classes and even cooking appliances. And no longer is haute cuisine the sole province of his signature restaurant. Now, you can get fried chicken and greens from Spago, Beverly Hills. On a recent weekend, the restaurant pulled in $2.5 million.

Give Managers Latitude

With 20 fine dining restaurants, 80 Express cafes and a catering service, Puck runs a large international operation and found that the crisis forced him to decentralize management. In a move that parallels the military’s mission command concept, Puck made his intent clear—to “give people an experience” and “grow every restaurant.” Then he entrusted the chefs and managers with the latitude to experiment, respond to the marketplace and make the best decisions for the customers, the menus and the business. “We are trying to use the Covid-19 crisis as an opportunity.”

It’s much easier for a large company with cash reserves and a diversified portfolio of products and services to weather a crisis. Apple is a case in point. It pivoted its supply chains and saw only momentary disruption in production. In fact, phone and watch sales are up. It’s made aggressive moves into cloud services, content creation and streaming video. Recently, the company invested in two of the world’s largest on-shore wind farms. In the midst of a recession, in the midst of a global pandemic, Apple’s stock has seen steady gains and its market capitalization is over $2 trillion.

Rather than sit in place, Apple has doubled down on its R&D. CEO Tim Cook: “We believe in investing during a downturn.” It’s not a new plan, it’s part of Apple’s DNA—innovate your way out of crisis. Cook’s predecessor, Steve Jobs, reacting to the financial crisis of 2008, said, “We’ve had one of these before, when the dot-com bubble burst. What I told our company was that we were just going to invest our way through the downturn… we were going to up our R&D budget so that we would be ahead of our competitors when the downturn was over. And it worked.”

Where most see danger, Cook, Rivera and Puck see opportunity, and their organizations are resilient enough to take advantage of it. Obviously, when hit by a pandemic, resilience becomes a key element of survival.

Most companies have some form of risk management. For a small business, it may be no more than an insurance policy. A large corporation might have an entire group dedicated to identifying, understanding and minimizing known risk. Resilience comes into play when the risk

is unknown.

Remember Eisenhower and planning? Do you understand your mission, your essential value proposition? Have you explored the contingencies? Have you built, or can you quickly establish, redundant systems? Are your processes and structures rigid or do they allow for flexibility and adaptation? Around your essential value proposition, can you reach different markets, build multiple sources of revenue?

Heraclitus said it a few thousand years ago: “The only constant in life is change.” Look forward to it. Seek the advantage it presents. Don’t wait for it to be “over.” Move.

Think of the whole and be prepared to shift your business systems. You mission may not change, but how you get there probably will. Count on collaboration and decentralization, and when you measure performance, look beyond the bottom line to the development of new or different approaches and capabilities. The bottom line is what happened yesterday.

And value diversity. Diversification has long been used as a hedge against the unknown. Where diversification will have the greatest impact on a company’s profitability, adaptability, creativity and resilience will not be in its products, its investments, or in its divisions, but in the composition of its workforce. That’s a fact. According to research by McKinsey, companies in the top quartile of ethnic and cultural diversity are 35 percent more likely to outperform their peers.

Building resilience may not be the most efficient way to run a business in the short run, but it’s a way to make sure you’re in it for the long run. If you don’t want to get hit again, you’d better move.

CULTIVATE AGILITY

Accelerate Change

Stan Harris

Associate Dean for Graduate Studies

Luck Professor

Department of Management at Harbert College of Business

Like other major disruptions, the COVID pandemic has required organizations to change and adapt—the quicker the better. But how can organizations shorten the time required to successfully change so they can be better prepared for the next disruption or opportunity?

The social psychologist Kurt Lewin offered one of the most enduring metaphors for the process of organizational change. In 1947, he observed that change progressed through three phases: unfreezing, changing, and refreezing.

Too often, organizations start in a fixed, fundamentally stable and “solid” state (the way things are), which must be “unfrozen” before they can be “changed.” Unfreezing is the process of getting the system ready for change and reducing sources of resistance. Changes must then be encouraged and reinforced so they stick and the organization can be “refrozen” in a new post-change state.

Lewin’s metaphor captures a sad truth: Most organizations find themselves rigid and entrenched in their operations, strategies, structures and policies when confronting challenges or opportunities that call for change. Wouldn’t it be easier to change, react and adapt if the organization were inherently more flexible and in a perpetual state of change-readiness? Luckily, there

are several things organizations can do to promote greater agility.

First, executives must believe, articulate and promote a vision championing flexibility but grounded in the organization’s core values, strengths and unique value proposition. This grounding provides a solid pivot point and source of resilience around which adaptation revolves. Continuous improvement and innovation are emphasized. However, talk is cheap and organizations must demonstrate their commitment through actions such as celebrating improvement efforts that fail as learning opportunities. Long-term efforts to build an organization that thrives should not be sacrificed for short-term demands.

Change-ready organizations have their pulse on what’s happening around them. They value and promote constant environmental scanning for opportunities and challenges. This awareness is supported by close, collaborative relationships with suppliers, customers and regulators who are often closest to the action.

Information and ideas within the organization must be free-flowing and employees at all levels must be encouraged to keep their eyes and ears open for challenges and opportunities. They must also feel comfortable sharing what they learn and their ideas for responding openly and honestly.

Two interrelated organizational features support this free flow of ideas. First, flatter organizations push responsibilities closer to those on the front lines; layers of hierarchy slow information sharing and response times. Second, employees must feel empowered to act within an overarching vision of pursuing excellence. Empowering everyone to act in the pursuit of a vision of excellence encourages teamwork, questioning, adaptability, communication, innovation and calculated risk taking. Such empowerment creates engaged and loyal employees and promotes organizational agility.

Organizations that fundamentally approach change positively and as a means for grabbing opportunities are perpetually unfrozen and ready to take advantage of whatever the world throws at them.