Ever deliberately instructed your children not to do something, and they did it anyway? Or perhaps you’ve noticed a few brazen drivers who have left their vehicles in front of a “no parking” sign?

Rules are made to be followed, but policy manuals and codes of ethics might be disregarded. We’d like to think that strong governance can deter fraud and other acts of malfeasance, but it doesn’t always work that way. In fact, research finds that it can have the opposite effect among top managers and CEOs.

Brian Connelly, Luck Eminent Scholar of Management in the Harbert College, co-authored an award-winning paper that reveals top managers may be more likely to engage in financial misconduct when facing stringent oversight.

“When people trust us, we are intrinsically motivated to behave appropriately toward them,” says Connelly, whose co-authored paper earned the 2017 Fraud Impact Award presented by the Houston, Texas, Chapter of Certified Fraud Examiners. “The problem comes when people trust us, but then monitor us closely. This sends conflicting messages about trust, and robs us of our intrinsic motivation to behave appropriately. As a result, too much monitoring backfires because we resent the monitoring.”

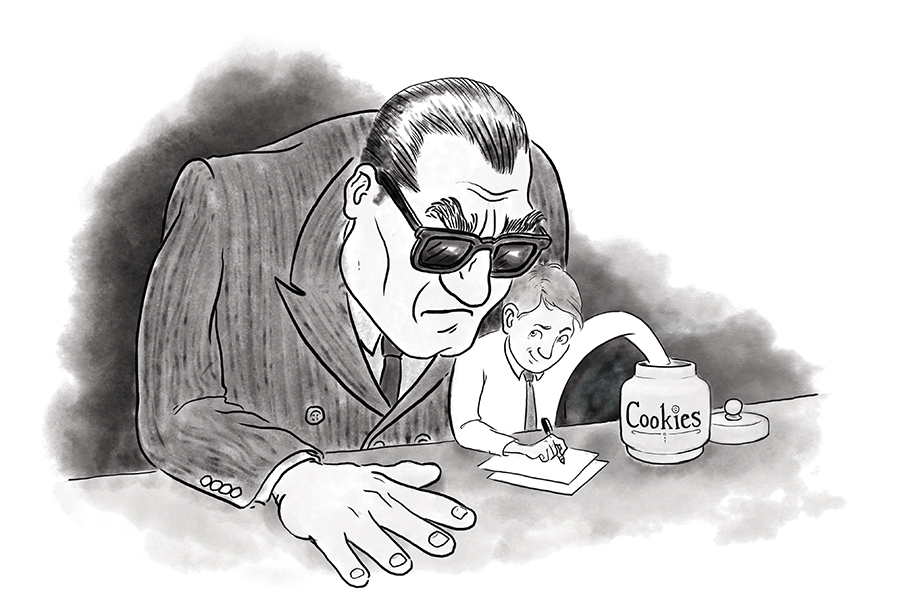

Simply put, this changes the nature of CEOs’ motivation for doing the right thing. When we do the right thing because Big Brother is watching, we might give in to temptation and run amok when Big Brother turns his head. In contrast, when we do the right thing for intrinsic reasons, Big Brother need not worry. Connelly says the job of a director is comparable to that of a parent because both are seeking the appropriate “balance between monitoring and autonomy.”

Connelly and his co-authors collected governance data from all S&P 1500 firms from 1999-2012 using a variety of accounting, auditing and securities agencies.

Connelly says he once asked Andy Fastow, former chief financial officer at Enron, whether he found it surprising that increased monitoring could lead to increased fraud. “He said that as monitoring increases they find more cases of fraud, but that doesn’t mean that more fraud is occurring—they are just finding what they are looking for,” Connelly says.

“Pick up the Wall Street Journal any day of the week and you will read about tremendously powerful shareholders. People like Carl Icahn, Warren Buffett, and Ralph Whitworth. These institutional investors have CEOs shaking in their boots. Over the past two decades or so, institutional investors have become the most powerful people on the planet. We wanted to examine some of the fallout of having these people looking over the shoulders of CEOs.”

The paper, “External Corporate Governance and Financial Fraud: Cognitive Evaluation Theory Insights on Agency Theory Prescriptions,” has been published by the Strategic Management Journal.