From the silent era to outrageous satire to gut-wrenching portrayals of corporate dilemmas. For nearly a century, film and television have chronicled the American workplace.

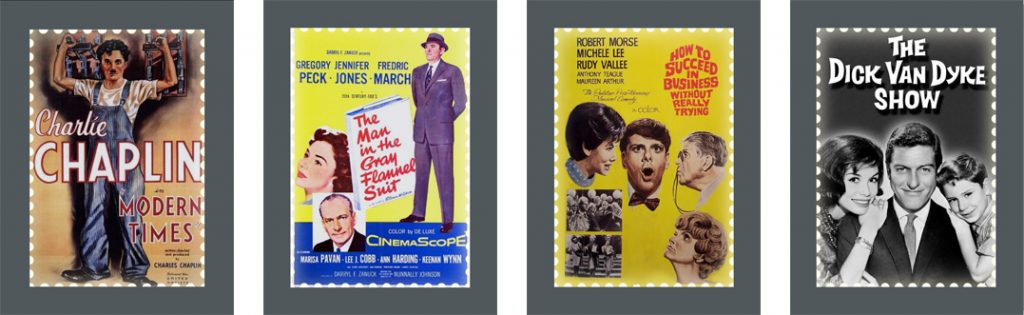

Charlie Chaplin’s “Modern Times” set off the genre in 1936. One of the last major silent movies, it follows the actor’s “Little Tramp” character — in his final onscreen appearance — as he endures the mechanized monolith of the industrial revolution. He gets trapped in giant gears, loses a race with an assembly line and later crusades for workers’ rights before ultimately walking away from it all. The movie was an indictment of the era’s inhumanity.

And it was eerily prescient of depictions of workplace discontent that would surface in the decades that followed.

In “The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit” (1956), Gregory Peck plays WWII vet Tom Rath, who lands a fast-track position at a highly influential company. Rath, a devoted family man, faces perhaps the first onscreen depiction of the work-life balance debacle. The job is prestigious and lucrative, but it turns Rath into a corporate drone, demanding his days, nights and weekends and alienating him from the idyllic post-war life he’d envisioned. Some 50 years later, TV’s “Mad Men” viewers would meet mid-century workaholic, alcoholic, womanizing ad exec Don Draper, who, in retrospect, might be seen as the anti-Rath.

The early ’60s comedy series “The Dick Van Dyke Show” focused on Rob Petrie (Van Dyke), a family man who spent his days at the writers’ table of a TV variety show, where he formed a work family of sorts, and his off time at home with his wife, Laura (Mary Tyler Moore) and their son. Laura, a stay–at-home mom who sometimes yearned for her former career as a dancer, seemed happy to host cocktail parties for friends and her husband’s colleagues, but she longed for more alone time with Rob, who was also, in a sense, married to his job. But the tone was whimsical, full of pratfalls and one-liners and memorable characters.

Whimsical doesn’t begin to describe the 1967 movie musical “How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying.” Ambitious young window-washer J. Pierrepont Finch strives to climb the corporate ladder of the building he’s been peering into. Watching it today can be cringe-worthy: At one point, secretaries launch into the song “A Secretary Is Not a Thing,” noting that “Her pad is to write in and not spend the night in,” along with a few hip shimmies. Cheery and raunchy, the film still gives viewers a feel for the office culture and what passed for humor at the time.

Finch, who makes his way up to vice president in charge of advertising, is played by Robert Morse, who 40 years later would portray elder statesman Bertram Cooper in “Mad Men,” which is set in the advertising world of the “How to Succeed . . .” era.

Pivot to 1970, and it’s a new world. “The Mary Tyler Moore Show” broke barriers, bringing 30-year-old divorcee Mary Richards into the offices of a Minneapolis TV station — not as a secretary, but as an associate news producer. Enter the independent, career-focused woman, surrounded not only by men — her boss, veteran newsman Lou Grant (Ed Asner), pompous news anchor Ted Baxter (Ted Knight) and deskmate Murray (Gavin MacLeod), but also a group of female peers, including her free-spirited friend Rhoda (Valerie Harper) and Sue Anne Nivens (Betty White), the flirtatious host of the “Happy Homemaker” show.

In “9 to 5,” a trio of vengeful, undervalued secretaries (played by Jane Fonda, Dolly Parton and Lily Tomlin) bring fury on their lecherous boss (Dabney Coleman), symbolically bringing down the corporate patriarchy. The ends to which the women go — kidnapping the boss, taking over the office — are outrageous. But their situation is not far from that of the secretaries of “How to Succeed in Business…” in the ’60s.

In “Wall Street” (1987) “Greed, for lack of a better word, is good.” That’s mogul Gordon Gekko’s mantra, which he not only lives by but also ingrains into the minds of his minions, including young protege Bud Fox (Charlie Sheen), whose life is swiftly upended. The movie, and Michael Douglas’s portrayal of the villainous Gekko, was an alarming inside look into the slate of ’80s corporate misdeeds that they’d only heard about from the outside. And it was a chilling view.

Director Oliver Stone never meant to present Gekko as a hero. But he was that for young guys hitting the stock market in the late ’90s, just before the dotcom bubble burst. A horde of rowdy 20-something guys riding high on ambition and testosterone populates the 2000 film “Boiler Room.” They bring in millions by selling nonexistent stocks to hapless targets, celebrating nightly with beer-fueled viewings of —what else — “Wall Street,” with the boys taking turns to quote, verbatim, every piece of dialogue in that movie. They were living the corporate dream . . . until the federal raids that ended their burgeoning careers.

The angst-ridden lives of cubicle-dwellers inspired Mike Judge’s 1999 comedy “Office Space.” Judge had done his time in that world, and maybe that’s why the movie resonated so well, with viewers actually rooting for a trio of would-be corporate criminals.

However, the movie is less about their devious plan and more about inane workplace culture. It’s now a cult classic satire piece about a nonsensical office life where pointless cover sheets on reports override any meaningful purpose, smarmy managers control hapless drones and souls are actively crushed — in the most hilarious way.

In “The Devil Wears Prada” (2006), young journalism grad Andy (Anne Hathaway) has big dreams of a career of crafting topical, thought-provoking pieces in high-end magazines. Instead, she finds herself working as an assistant to the editor of major fashion magazine Runway. At first she resists, but in time she becomes identical to her expensively styled coworkers and chained to her phone to satisfy every last ridiculous whim of her boss, Miranda Priestly (Meryl Streep), the icy, all-powerful editor and leading villain of the film.

Priestly rivaled any villainous male of movies past; a simple stare or understated word could signal the end of a career. In the end, Andy sees Miranda as a pioneer who turned a fashion magazine into a global empire. Miranda, for all her eloquent hurling of insults, respects Andy’s talent, work ethic and determination to stick to her original dreams. Andy walks away a changed person — but still herself.

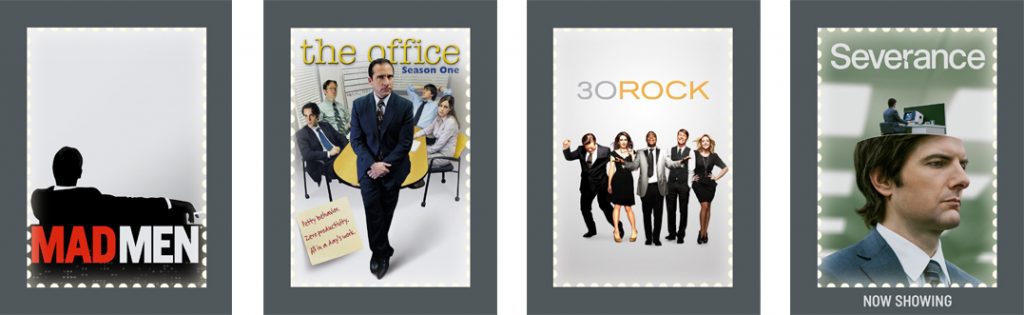

In 2005, the American version of “The Office” ushered in a new era of workplace entertainment for the mid-2000s. Its innovative mockumentary style gave us an up-close and personal look at the eccentric, endearing and sometimes maddening employees of a middling paper company, with cynicism and cringe in abundance. Michael Scott, regional manager of the Scranton office of flailing paper company Dunder-Mifflin, is still referenced in conversations about the ridiculousness of office life, as are characters like Dwight, Jim and the rest, almost 10 years after the show ended.

In “30 Rock” (2006) Liz Lemon (Tina Fey) is the head writer — and lone woman — on a team that writes for a sketch comedy TV show. With an arrogant boss (Alec Baldwin) and a mentally unstable star (Tracy Morgan), her teetering work-life balance keeps her at the edge of sanity. With a joke-a-minute script and a lineup of wacky side characters, the show could be seen as a modern-day retelling of the life of Rob Petrie in “The Dick Van Dyke Show” some 40 years later.

The 2007 series “Mad Men,” set in the 1960s, followed uber-successful Manhattan ad exec Don Draper through booze-drenched work lunches, countless infidelities, workaholism and an insatiable narcissistic craving for . . . something unattainable. Don chose the other path, the one not taken by Tom Rath in “The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit” 50 years before.

“The Intern” (2015) breaks old stereotypes of age-experience and superior-subordinate relationships, The film centers on Ben (Robert De Niro), a 70-year-old retiree who re-enters the corporate world as a senior intern at an online fashion retailer. He’s the apprentice of Jules (Anne Hathaway) and surrounded by millennial colleagues who initially see only stereotypes and distance themselves. But Ben, it turns out, belongs there, and teaches Jules and the other young employees more than they could ever have taught each other. The film reverse-mirrors “The Devil Wears Prada,” and not just because it’s Anne Hathaway in the boss’s office this time. It’s one generation learning from another, individuals discovering new facets of themselves on the job.

“Severance,” a breakout hit series of 2022, offers a surreal, but seemingly all too real, look into our current obsession with work-life balance, with a crucial sci-fi twist.

The premise brings to mind a pivotal scene in “Office Space” where Peter half-jokingly asks a hypnotherapist, “So is there any way that you could sort of just zonk me out so that I don’t know that I’m at work . . . in here?” And he points to his head. “Could I come home and think that I’ve been fishing all day, or . . . something?” To which the therapist replies, “That’s not really what I do, Peter.”

Twenty-three years later, “Severance” debuts on Apple TV+. And it turns out that is what they do. Minus the fishing. Through a vaguely referenced brain procedure, an employee can choose to sever work life from personal life. Viewers are privy to both the “outie” and “innie” lives of a group of coworkers performing bizarre tasks in a surreal office setting; their counterparts go on with their own lives, oblivious to it all.

And then there are dramas based on real-life, headline-making business debacles: “The Dropout,” chronicling the incredible rise and fall of Theranos and its delusional founder, Elizabeth Holmes; “Super Pumped,” about the roller coaster ride of starting Uber; and “WeCrashed,” telling the tale of the would-be world-changing company WeWork (the plot is in the title).

Could this signal a trend of dramatizing the real-life pitfalls of emerging tech companies? We’ll have to watch and see.

—Teri Greene